Locally Weighted Regression and Probabilistic Interpretation

Implementing Locally Weighted Regression with Skewed Data and Justifying the Use of Least Squares in Linear Models.

In this article I'll be explaining the following 2 topics in depth

Locally Weighted Regression

Probabilistic Interpretation to prove least square error is optimal for linear regression

Locally Weighted Regression

Previously, in my linear regression blog, we saw how to apply linear regression to find the parameters theta for data that is linearly distributed.

However, in situations where the data is not linearly distributed and has random ups and downs, we can't rely on the entire dataset to estimate our parameters. In such cases, we use the underlying data to update our parameters.

By using specific mathematical formulas and practices, we can modify our gradient descent formula to consider the data itself and adjust our parameters accordingly. Let's understand this graphically before we dive into the mathematics.

This is a beginner's course, so I'll explain everything as simply as possible. Let's start by looking at our linear regression graph.

The line of best fit to the hypothesis line fits our data well because the data is linearly distributed.

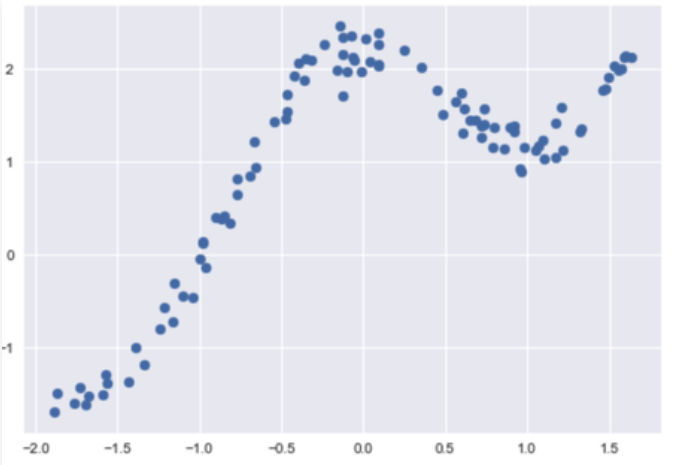

But if our data were distributed like this:

Then, fitting a straight line to this data doesn't seem to be the best way to make predictions. Instead, we can fit multiple lines to this dataset to make more accurate predictions, as shown below.

By using four different lines, I can make good predictions of y values for a certain range of x values. For example, for x ranging from -1.0 to 0.0, I can use the second line as my line of best fit to make accurate predictions.

That's the idea behind locally weighted regression. We don't actually predict four different lines; instead, we look at the data "local" to the point we're trying to predict and adjust our parameters to fit the local data.

For locally weighted regression:

We fit the parameters θ to minimise a slightly different cost function J(θ), which is

$$J(\theta) = \sum_{i=0}^{m} w_i \frac{(y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}{2}$$

Which is different from the previously used

$$J(\theta) = \frac{1}{2}\sum(y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2$$

So the updated gradient descent algorithm to update our θ value would be

$$\displaylines{ \theta_j : = \theta_j - \alpha \frac{\partial}{\partial \; \theta_j} J(\theta) \\ \\ \theta_j := \theta_j - \alpha \sum w^{(i)}(h_θ(x^i) - y^j)x_j^i) \\ here \;\; w^{(i)} \;\; is \;\; some \;\; weight }$$

Here, the weight is a constant value with respect to theta, so it simply gets multiplied. If you want to understand the math behind the gradient descent algorithm derivation, refer to my linear regression blog.

The key element for locally weighted regression is the weight ( w ), which is the core of this algorithm.

The equation for the weight ( w ) is

$$w_i = \exp(\frac{-(x_i - x)^2}{2\; \tau^2})$$

The T (tau) determines the bandwidth or localness of the algorithm. (I'll explain this more clearly in the next segment) Now,

if (xᵢ - x) is small, the weight will be almost equal to 1, which will significantly affect the parameter update.

- This allows us to give importance to data that is close to the point x we're trying to estimate the y value for.

if (xᵢ - x) is large, the weight will be almost equal to 0, which will have almost no effect on the parameter update.

Bandwidth or Localness of the algorithm:

Now, as I mentioned earlier, "the localness of the algorithm" refers to the weight equation itself. When we examine this equation closely,

$$w_i = \exp(\frac{-(x_i - x)^2}{2\; \tau^2})$$

We can see that this equation is similar to the Gaussian distribution equation, also known as the normal distribution equation.

$$f(x) = \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{-\frac{1}{2}(\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma})^2}$$

This equation integrates to 1, but our equation does not, so it is not a normal distribution. However, it's important to note this because the normal distribution resembles a bell-shaped curve, as shown below.

The width of the bell curve depends on the σ (sigma) value. In our case, this is the T (tau) value. By choosing an appropriate tau value, we can determine how far each point can be for the weight to influence the determination of the parameter theta values.

So in theory

The data points outside the green lines [(less than -1.0) and (above 1.5)] are of no importance, the points lying between the red and green line [ (-1.0 to -0.5) and (0.5 to 1.0) ] are of less importance and the points inside the red lines (-0.5 to 0.5) are of significant importance.

Now the code for the gradient descent of locally weighted regression would be

$$\displaylines{ \theta_j := \theta_j - \alpha \sum w^{(i)}(h_θ(x^i) - y^j)x_j^i) }$$

def GradientDescent(theta, X, y, x, tau=0.1, alpha=0.01, epochs=300):

for _ in range(epochs):

for j in range(len(theta)):

error = 0

for i in range(len(X)):

h = X.dot(theta)

weight = np.exp(((-(X[i][0] - x)**2) / (2 * (tau*tau))))

error += weight * (h[i][0] - y[i][0]) * (X[i][0])

theta[j] -= alpha * error

Probabilistic Interpretation

In my linear regression blog, We have used the least square error for our cost function, In this section we'll see why the least square error is preferred mathematically.

Now let's assume

$$y^{(i)} = \theta^Tx^{(i)} + ε^{(i)}$$

The ε is error and it is gaussian distributed with mean as 0 and standard deviation as σ.

$$ε^{(i)} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)$$

Therefore,

$$\displaylines{ y^{(i)} = \theta^Tx^{(i)} + ε^{(i)} \\ => ε^{(i)} = y^{(i)} - \theta^T x^{(i)} \\ P(ε^{(i)}) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}\exp(-\frac{(ε^{i})^2}{2\sigma^2}) \\ P(y^i | x^i; \theta) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}\exp(\frac{-(y^{(i)} - \theta^T x^{(i)})^2}{2\sigma^2}) \\ Let \;\; \mathcal{L}(\theta) = P(\hat{y} | x;\theta) \\ = \prod_{i=1}^m P(y^{(i)}|x^{(i)};\theta) \\ here \;\; we \;\; assumed \;\; that \;\; errors \;\; are \;\; IID \\ \;[Independently\;\;and\;\;Identically\;\;Distributed]\;\; \\ = \prod_{i=1}^m \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\exp{\frac{-(y^{(i)} - \theta^Tx^{(i)})}{2\sigma^2}}} \\ let's \;\; assume \;\; \\ \mathcal{l}(\theta) = log\; \mathcal{L}(\theta) \\ => log \prod_{i=1}^m \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}\exp(\frac{-(y^{(i)} - \theta^T x^{(i)})^2}{2\sigma^2}) \\ \sum_{i=1}^m (log(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}) + log(\exp[\frac{-(y^{(i)} - \theta^T x^{(i)})^2}{2\sigma^2}])) \\ log \;\; of \;\; products \;\; = sum \;\; of \;\; logs \\ = m log(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma})+\sum - \frac{(y^{(i)} - \theta^T x^{(i)})^2}{2\sigma^2} \\ }$$

Here σ does not affect out theta value so we ignore it and therefore the equation we get is

$$\sum_{i=1}^m - \frac{1}{2}(y^{(i)} - \theta^T x^{(i)})^2$$

Which is equal to our cost function J(θ)

This is mathematical proof that least square is optimal for linear regressions but of course it's case sensitive.

And that's it for locally weighted regression and probabilistic interpretation

I'll be teaching about Logistic Regression in my next article, so stay tuned!

If you enjoyed this article, please consider buying me a coffee.

Follow me on my social media and consider subscribing, as I'll be covering more Machine Learning algorithms "from scratch".